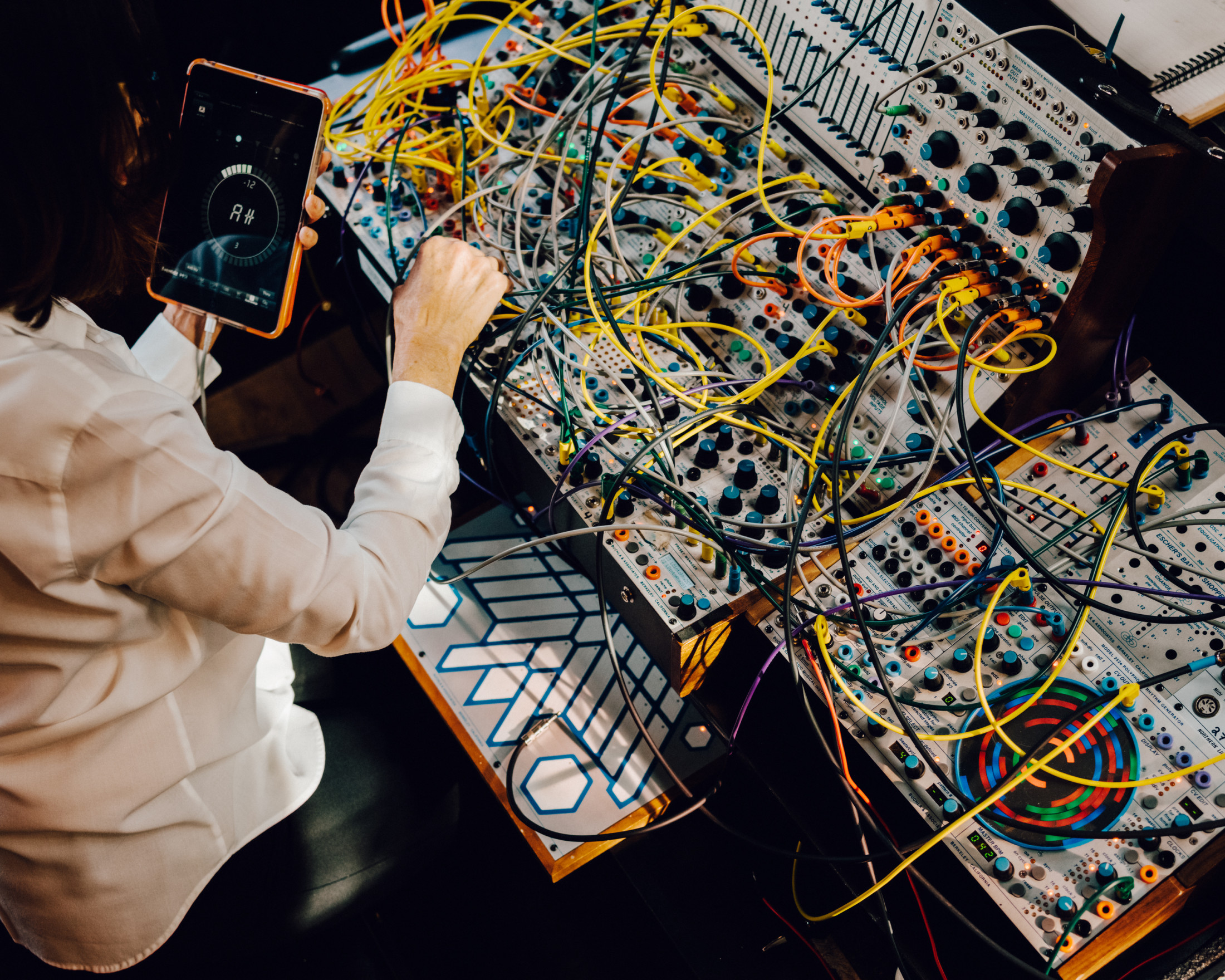

Suzanne Ciani is one of electronic music's earliest and most influential figures. She is also, it turns out, a lovely person to interview. A few days after our photographer Jake Stangel paid a visit to her idyllic oceanside home in Northern California, we caught up with Ciani by phone. She was warm, open and—despite her busy work schedule—seemed genuinely eager to talk. In a lilting voice that reminded us of our high school art teacher, the five-time Grammy-nominee chatted about her journey from classical music scholar to 1970s synth pioneer, her tempestuous on-again/off-again relationship with her instrument, the Buchla, and why analogue electronic sound is (finally) having its moment. Below, a condensed version of our conversation.

Hi Suzanne! The portraits that Jake took of you are so beautiful.

Oh, really? Wow. I was in a bad mood that day. I think I had just paid my taxes.

Well, it gave you a poetic moodiness. And your home in Bolinas looks amazing. Are you there now?

Yes. I've actually been here for more than 25 years, which is completely shocking. I think I've been here longer than I've been anywhere.

Why have you stuck around that long?

I'm a prisoner of beauty. I live in an extraordinary spot on the very fringe of the West Coast. I know it's not the real world because I lived in New York for 19 years.

Jake was curious if the proximity to the ocean influenced your work.

Oh absolutely, my music has always been about the ocean, the waves. My first self-produced Buchla album was called “Seven Waves.” The wave was a compositional form for me, a symbol of a new kind of rhythm that’s slow, very sensual, very feminine.

You returned to the Buchla only recently. Why did you stop playing?

My Buchla met a bad fate. It was the 200 system, which I was in love with. I mean, true love. Half of it got stolen, and then the other half was broken in transit. And in those days, nobody in New York knew how to fix a Buchla.

The funny thing is that about 10 years ago the stolen part of the Buchla reappeared. Somebody sent me a picture of it. It had been sent to them to be repaired. I mean, I fainted when I saw it, I truly fainted. It was a messy situation and I never got it back. I’m always amazed by how cloak-and-dagger the whole electronic world can be.

So there was a long period of time where you were Buchla-less?

Yes, and then when I came back to the West Coast in 1992 I reconnected with Don Buchla. One day he called and said, “Look, if you're ever thinking about going back, now is the time, because I'm going to sell the company.” He encouraged me to put together a system and I did. I reconfigured a 200e. Then it sat there for about a year, I wasn't interested. But these things, they're evolutionary. Things just kind of grow, and I started a relationship with the machine, and then Don died.